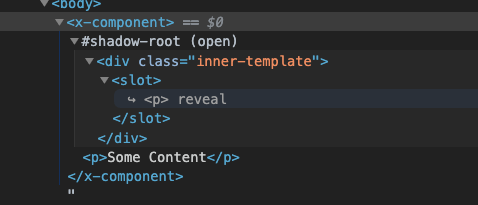

Slot elements can be placed anywhere within the component. It is preferred that those slots are named (if only one slot exists, the name can be omitted). This is what a web component with slots would look like. Using slots means that I would be doing just passing HTML and I don't think there is an easy way to iterate through HTML list items. Component I can keep on using components but now I have to convert my old list to an object and add some conditionals to manage to prepare the component for handling HTML formating. Font-face-name; missing-glyph; The list of names above is the summary of all hyphen-containing element names from the applicable specifications, namely SVG and MathML. If you want to check if a given string is a valid custom element name, check Mathias Bynens's app.

- Web Components Named Slots No Deposit

- Web Components Named Slots Games

- Web Components Named Slots Real Money

What are Components?

Components are one of the most powerful features of Vue.js. They help you extend basic HTML elements to encapsulate reusable code. At a high level, Components are custom elements that Vue.js’ compiler would attach specified behavior to. In some cases, they may also appear as a native HTML element extended with the special is attribute.

Using Components

Registration

We’ve learned in the previous sections that we can create a component constructor using Vue.extend():

To use this constructor as a component, you need to register it with Vue.component(tag, constructor):

Note that Vue.js does not enforce the W3C rules for custom tag-names (all-lowercase, must contain a hyphen) though following this convention is considered good practice.

Once registered, the component can now be used in a parent instance’s template as a custom element, <my-component>. Make sure the component is registered before you instantiate your root Vue instance. Here’s the full example:

Which will render:

Note the component’s template replaces the custom element, which only serves as a mounting point. This behavior can be configured using the replace instance option.

Also note that components are provided a template instead of mounting with the el option! Only the root Vue instance (defined using new Vue) will include an el to mount to).

Local Registration

You don’t have to register every component globally. You can make a component available only in the scope of another component by registering it with the components instance option:

The same encapsulation applies for other assets types such as directives, filters and transitions.

Registration Sugar

To make things easier, you can directly pass in the options object instead of an actual constructor to Vue.component() and the component option. Vue.js will automatically call Vue.extend() for you under the hood:

Component Option Caveats

Most of the options that can be passed into the Vue constructor can be used in Vue.extend(), with two special cases: data and el. Imagine we simply pass an object as data to Vue.extend():

The problem with this is that the same data object will be shared across all instances of MyComponent! This is most likely not what we want, so we should use a function that returns a fresh object as the data option:

The el option also requires a function value when used in Vue.extend(), for exactly the same reason.

Template Parsing

Vue.js template engine is DOM-based and uses native parser that comes with the browser instead of providing a custom one. There are benefits to this approach when compared to string-based template engines, but there are also caveats. Templates have to be individually valid pieces of HTML. Some HTML elements have restrictions on what elements can appear inside them. Most common of these restrictions are:

Web Components Named Slots No Deposit

acan not contain other interactive elements (e.g. buttons and other links)lishould be a direct child ofulorol, and bothulandolcan only containlioptionshould be a direct child ofselect, andselectcan only containoption(andoptgroup)tablecan only containthead,tbody,tfootandtr, and these elements should be direct children oftabletrcan only containthandtd, and these elements should be direct children oftr

In practice these restriction can cause unexpected behavior. Although in simple cases it might appear to work, you can not rely on custom elements being expanded before browser validation. E.g. <my-select><option>...</option></my-select> is not a valid template even if my-select component eventually expands to <select>...</select>.

Another consequence is that you can not use custom tags (including custom elements and special tags like <component>, <template> and <partial>) inside of select, table and other elements with similar restrictions. Custom tags will be hoisted out and thus not render properly.

In case of a custom element you should use the is special attribute:

In case of a <template> inside of a <table> you should use <tbody>, as tables are allowed to have multiple tbody:

Props

Passing Data with Props

Every component instance has its own isolated scope. This means you cannot (and should not) directly reference parent data in a child component’s template. Data can be passed down to child components using props.

A “prop” is a field on a component’s data that is expected to be passed down from its parent component. A child component needs to explicitly declare the props it expects to receive using the props option:

Then, we can pass a plain string to it like so:

Result:

camelCase vs. kebab-case

HTML attributes are case-insensitive. When using camelCased prop names as attributes, you need to use their kebab-case (hyphen-delimited) equivalents:

Dynamic Props

Similar to binding a normal attribute to an expression, we can also use v-bind for dynamically binding props to data on the parent. Whenever the data is updated in the parent, it will also flow down to the child:

It is often simpler to use the shorthand syntax for v-bind:

Result:

Literal vs. Dynamic

A common mistake beginners tend to make is attempting to pass down a number using the literal syntax:

However, since this is a literal prop, its value is passed down as a plain string '1', instead of an actual number. If we want to pass down an actual JavaScript number, we need to use the dynamic syntax to make its value be evaluated as a JavaScript expression:

Prop Binding Types

By default, all props form a one-way-down binding between the child property and the parent one: when the parent property updates, it will flow down to the child, but not the other way around. This default is meant to prevent child components from accidentally mutating the parent’s state, which can make your app’s data flow harder to reason about. However, it is also possible to explicitly enforce a two-way or a one-time binding with the .sync and .oncebinding type modifiers:

Compare the syntax:

The two-way binding will sync the change of child’s msg property back to the parent’s parentMsg property. The one-time binding, once set up, will not sync future changes between the parent and the child.

Note that if the prop being passed down is an Object or an Array, it is passed by reference. Mutating the Object or Array itself inside the child will affect parent state, regardless of the binding type you are using.

Prop Validation

It is possible for a component to specify the requirements for the props it is receiving. This is useful when you are authoring a component that is intended to be used by others, as these prop validation requirements essentially constitute your component’s API, and ensure your users are using your component correctly. Instead of defining the props as an array of strings, you can use the object hash format that contain validation requirements:

The type can be one of the following native constructors:

- String

- Number

- Boolean

- Function

- Object

- Array

In addition, type can also be a custom constructor function and the assertion will be made with an instanceof check.

When a prop validation fails, Vue will refuse to set the value on the child component, and throw a warning if using the development build.

Parent-Child Communication

Parent Chain

A child component holds access to its parent component as this.$parent. A root Vue instance will be available to all of its descendants as this.$root. Each parent component has an array, this.$children, which contains all its child components.

Although it’s possible to access any instance in the parent chain, you should avoid directly relying on parent data in a child component and prefer passing data down explicitly using props. In addition, it is a very bad idea to mutate parent state from a child component, because:

It makes the parent and child tightly coupled;

It makes the parent state much harder to reason about when looking at it alone, because its state may be modified by any child! Ideally, only a component itself should be allowed to modify its own state.

Custom Events

All Vue instances implement a custom event interface that facilitates communication within a component tree. This event system is independent from the native DOM events and works differently.

Each Vue instance is an event emitter that can:

Listen to events using

$on();Trigger events on self using

$emit();Dispatch an event that propagates upward along the parent chain using

$dispatch();Broadcast an event that propagates downward to all descendants using

$broadcast().

Unlike DOM events, Vue events will automatically stop propagation after triggering callbacks for the first time along a propagation path, unless the callback explicitly returns true.

A simple example:

v-on for Custom Events

The example above is pretty nice, but when we are looking at the parent’s code, it’s not so obvious where the 'child-msg' event comes from. It would be better if we can declare the event handler in the template, right where the child component is used. To make this possible, v-on can be used to listen for custom events when used on a child component:

This makes things very clear: when the child triggers the 'child-msg' event, the parent’s handleIt method will be called. Any code that affects the parent’s state will be inside the handleIt parent method; the child is only concerned with triggering the event.

Child Component Refs

Despite the existence of props and events, sometimes you might still need to directly access a child component in JavaScript. To achieve this you have to assign a reference ID to the child component using v-ref. For example:

When v-ref is used together with v-for, the ref you get will be an Array or an Object containing the child components mirroring the data source.

Content Distribution with Slots

When using components, it is often desired to compose them like this:

There are two things to note here:

The

<app>component does not know what content may be present inside its mount target. It is decided by whatever parent component that is using<app>.The

<app>component very likely has its own template.

To make the composition work, we need a way to interweave the parent “content” and the component’s own template. This is a process called content distribution (or “transclusion” if you are familiar with Angular). Vue.js implements a content distribution API that is modeled after the current Web Components spec draft, using the special <slot> element to serve as distribution outlets for the original content.

Compilation Scope

Before we dig into the API, let’s first clarify which scope the contents are compiled in. Imagine a template like this:

Should the msg be bound to the parent’s data or the child data? The answer is parent. A simple rule of thumb for component scope is:

Everything in the parent template is compiled in parent scope; everything in the child template is compiled in child scope.

A common mistake is trying to bind a directive to a child property/method in the parent template:

Assuming someChildProperty is a property on the child component, the example above would not work as intended. The parent’s template should not be aware of the state of a child component.

If you need to bind child-scope directives on a component root node, you should do so in the child component’s own template:

Similarly, distributed content will be compiled in the parent scope.

Single Slot

Parent content will be discarded unless the child component template contains at least one <slot> outlet. When there is only one slot with no attributes, the entire content fragment will be inserted at its position in the DOM, replacing the slot itself.

Anything originally inside the <slot> tags is considered fallback content. Fallback content is compiled in the child scope and will only be displayed if the hosting element is empty and has no content to be inserted.

Suppose we have a component with the following template:

Parent markup that uses the component:

The rendered result will be:

Named Slots

<slot> elements have a special attribute, name, which can be used to further customize how content should be distributed. You can have multiple slots with different names. A named slot will match any element that has a corresponding slot attribute in the content fragment.

There can still be one unnamed slot, which is the default slot that serves as a catch-all outlet for any unmatched content. If there is no default slot, unmatched content will be discarded.

For example, suppose we have a multi-insertion component with the following template:

Parent markup:

The rendered result will be:

The content distribution API is a very useful mechanism when designing components that are meant to be composed together.

Dynamic Components

You can use the same mount point and dynamically switch between multiple components by using the reserved <component> element and dynamically bind to its is attribute:

keep-alive

If you want to keep the switched-out components alive so that you can preserve its state or avoid re-rendering, you can add a keep-alive directive param:

activate Hook

Web Components Named Slots Games

When switching components, the incoming component might need to perform some asynchronous operation before it should be swapped in. To control the timing of component swapping, implement the activate hook on the incoming component:

Note the activate hook is only respected during dynamic component swapping or the initial render for static components - it does not affect manual insertions with instance methods.

transition-mode

The transition-mode param attribute allows you to specify how the transition between two dynamic components should be executed.

By default, the transitions for incoming and outgoing components happen simultaneously. This attribute allows you to configure two other modes:

in-out: New component transitions in first, current component transitions out after incoming transition has finished.out-in: Current component transitions out first, new component transitions in after outgoing transition has finished.

Example

Misc

Components and v-for

You can directly use v-for on the custom component, like any normal element:

However, this won’t pass any data to the component, because components have isolated scopes of their own. In order to pass the iterated data into the component, we should also use props:

The reason for not automatically injecting item into the component is because that makes the component tightly coupled to how v-for works. Being explicit about where its data comes from makes the component reusable in other situations.

Authoring Reusable Components

When authoring components, it is good to keep in mind whether you intend to reuse this component somewhere else later. It is OK for one-off components to have some tight coupling with each other, but reusable components should define a clean public interface.

The API for a Vue.js component essentially comes in three parts - props, events and slots:

Props allow the external environment to feed data to the component;

Events allow the component to trigger actions in the external environment;

Slots allow the external environment to insert content into the component’s view structure.

With the dedicated shorthand syntax for v-bind and v-on, the intents can be clearly and succinctly conveyed in the template:

Async Components

In large applications, we may need to divide the app into smaller chunks, and only load a component from the server when it is actually needed. To make that easier, Vue.js allows you to define your component as a factory function that asynchronously resolves your component definition. Vue.js will only trigger the factory function when the component actually needs to be rendered, and will cache the result for future re-renders. For example:

The factory function receives a resolve callback, which should be called when you have retrieved your component definition from the server. You can also call reject(reason) to indicate the load has failed. The setTimeout here is simply for demonstration; How to retrieve the component is entirely up to you. One recommended approach is to use async components together with Webpack’s code-splitting feature:

Assets Naming Convention

Some assets, such as components and directives, appear in templates in the form of HTML attributes or HTML custom tags. Since HTML attribute names and tag names are case-insensitive, we often need to name our assets using kebab-case instead of camelCase, which can be a bit inconvenient.

Vue.js actually supports naming your assets using camelCase or PascalCase, and automatically resolves them as kebab-case in templates (similar to the name conversion for props):

This works nicely with ES6 object literal shorthand:

Recursive Component

Components can recursively invoke itself in its own template, however, it can only do so when it has the name option:

A component like the above will result in a “max stack size exceeded” error, so make sure recursive invocation is conditional. When you register a component globally using Vue.component(), the global ID is automatically set as the component’s name option.

Fragment Instance

Web Components Named Slots Real Money

When you use the template option, the content of the template will replace the element the Vue instance is mounted on. It is therefore recommended to always have a single root-level, plain element in templates.

Instead of templates like this:

Prefer this:

There are multiple conditions that will turn a Vue instance into a fragment instance:

- Template contains multiple top-level elements.

- Template contains only plain text.

- Template contains only another component (which can potentially be a fragment instance itself).

- Template contains only an element directive, e.g.

<partial>or vue-router’s<router-view>. - Template root node has a flow-control directive, e.g.

v-iforv-for.

The reason is that all of the above cause the instance to have an unknown number of top-level elements, so it has to manage its DOM content as a fragment. A fragment instance will still render the content correctly. However, it will not have a root node, and its $el will point to an “anchor node”, which is an empty Text node (or a Comment node in debug mode).

What’s more important though, is that non-flow-control directives, non-prop attributes and transitions on the component element will be ignored, because there is no root element to bind them to:

There are, of course, valid use cases for fragment instances, but it is in general a good idea to give your component template a single, plain root element. It ensures directives and attributes on the component element to be properly transferred, and also results in slightly better performance.

Inline Template

When the inline-template special attribute is present on a child component, the component will use its inner content as its template, rather than treating it as distributed content. This allows more flexible template-authoring.

However, inline-template makes the scope of your templates harder to reason about, and makes the component’s template compilation un-cachable. As a best practice, prefer defining templates inside the component using the template option.

Smashing Newsletter

Every week, we send out useful front-end & UX techniques. Subscribe and get the Smart Interface Design Checklists PDF delivered to your inbox.

With the recent release of Vue 2.6, the syntax for using slots has been made more succinct. This change to slots has gotten me re-interested in discovering the potential power of slots to provide reusability, new features, and clearer readability to our Vue-based projects. What are slots truly capable of?

If you’re new to Vue or haven’t seen the changes from version 2.6, read on. Probably the best resource for learning about slots is Vue’s own documentation, but I’ll try to give a rundown here.

What Are Slots?

Slots are a mechanism for Vue components that allows you to compose your components in a way other than the strict parent-child relationship. Slots give you an outlet to place content in new places or make components more generic. The best way to understand them is to see them in action. Let’s start with a simple example:

This component has a wrapper div. Let’s pretend that div is there to create a stylistic frame around its content. This component is able to be used generically to wrap a frame around any content you want. Let’s see what it looks like to use it. The frame component here refers to the component we just made above.

The content that is between the opening and closing frame tags will get inserted into the frame component where the slot is, replacing the slot tags. This is the most basic way of doing it. You can also specify default content to go into a slot simply by filling it in:

So now if we use it like this instead:

The default text of “This is the default content if nothing gets specified to go here” will show up, but if we use it as we did before, the default text will be overridden by the img tag.

Multiple/Named Slots

You can add multiple slots to a component, but if you do, all but one of them is required to have a name. If there is one without a name, it is the default slot. Here’s how you create multiple slots:

We kept the same default slot, but this time we added a slot named header where you can enter a title. You use it like this:

Just like before, if we want to add content to the default slot, just put it directly inside the titled-frame component. To add content to a named slot, though, we needed to wrap the code in a template tag with a v-slot directive. You add a colon (:) after v-slot and then write the name of the slot you want the content to be passed to. Note that v-slot is new to Vue 2.6, so if you’re using an older version, you’ll need to read the docs about the deprecated slot syntax.

Scoped Slots

One more thing you’ll need to know is that slots can pass data/functions down to their children. To demonstrate this, we’ll need a completely different example component with slots, one that’s even more contrived than the previous one: let’s sorta copy the example from the docs by creating a component that supplies the data about the current user to its slots:

This component has a property called user with details about the user. By default, the component shows the user’s last name, but note that it is using v-bind to bind the user data to the slot. With that, we can use this component to provide the user data to its descendant:

To get access to the data passed to the slot, we specify the name of the scope variable with the value of the v-slot directive.

There are a few notes to take here:

- We specified the name of

default, though we don’t need to for the default slot. Instead we could just usev-slot='slotProps'. - You don’t need to use

slotPropsas the name. You can call it whatever you want. - If you’re only using a default slot, you can skip that inner

templatetag and put thev-slotdirective directly onto thecurrent-usertag. - You can use object destructuring to create direct references to the scoped slot data rather than using a single variable name. In other words, you can use

v-slot='{user}'instead ofv-slot='slotProps'and then you can useuserdirectly instead ofslotProps.user.

Taking those notes into account, the above example can be rewritten like this:

A couple more things to keep in mind:

- You can bind more than one value with

v-binddirectives. So in the example, I could have done more than justuser. - You can pass functions to scoped slots too. Many libraries use this to provide reusable functional components as you’ll see later.

v-slothas an alias of#. So instead of writingv-slot:header='data', you can write#header='data'. You can also just specify#headerinstead ofv-slot:headerwhen you’re not using scoped slots. As for default slots, you’ll need to specify the name ofdefaultwhen you use the alias. In other words, you’ll need to write#default='data'instead of#='data'.

There are a few more minor points you can learn about from the docs, but that should be enough to help you understand what we’re talking about in the rest of this article.

What Can You Do With Slots?

Slots weren’t built for a single purpose, or at least if they were, they’ve evolved way beyond that original intention to be a powerhouse tool for doing many different things.

Reusable Patterns

Components were always designed to be able to be reused, but some patterns aren’t practical to enforce with a single “normal” component because the number of props you’ll need in order to customize it can be excessive or you’d need to pass large sections of content and potentially other components through the props. Slots can be used to encompass the “outside” part of the pattern and allow other HTML and/or components to placed inside of them to customize the “inside” part, allowing the component with slots to define the pattern and the components injected into the slots to be unique.

For our first example, let’s start with something simple: a button. Imagine you and your team are using Bootstrap*. With Bootstrap, your buttons are often strapped with the base `btn` class and a class specifying the color, such as `btn-primary`. You can also add a size class, such as `btn-lg`.

* I neither encourage nor discourage you from doing this, I just needed something for my example and it’s pretty well known.

Let’s now assume, for simplicity’s sake that your app/site always uses btn-primary and btn-lg. You don’t want to always have to write all three classes on your buttons, or maybe you don’t trust a rookie to remember to do all three. In that case, you can create a component that automatically has all three of those classes, but how do you allow customization of the content? A prop isn’t practical because a button tag is allowed to have all kinds of HTML in it, so we should use a slot.

Now we can use it everywhere with whatever content you want:

Of course, you can go with something much bigger than a button. Sticking with Bootstrap, let’s look at a modal, or least the HTML part; I won’t be going into functionality… yet.

Now, let’s use this:

The above type of use case for slots is obviously very useful, but it can do even more.

Reusing Functionality

Vue components aren’t all about the HTML and CSS. They’re built with JavaScript, so they’re also about functionality. Slots can be useful for creating functionality once and using it in multiple places. Let’s go back to our modal example and add a function that closes the modal:

Now when you use this component, you can add a button to the footer that can close the modal. Normally, in the case of a Bootstrap modal, you could just add data-dismiss='modal' to a button, but we want to hide Bootstrap specific things away from the components that will be slotting into this modal component. So we pass them a function they can call and they are none the wiser about Bootstrap’s involvement:

Renderless Components

And finally, you can take what you know about using slots to pass around reusable functionality and strip practically all of the HTML and just use the slots. That’s essentially what a renderless component is: a component that provides only functionality without any HTML.

Making components truly renderless can be a little tricky because you’ll need to write render functions rather than using a template in order to remove the need for a root element, but it may not always be necessary. Let’s take a look at a simple example that does let us use a template first, though:

This is an odd example of a renderless component because it doesn’t even have any JavaScript in it. That’s mostly because we’re just creating a pre-configured reusable version of a built-in renderless function: transition.

Yup, Vue has built-in renderless components. This particular example is taken from an article on reusable transitions by Cristi Jora and shows a simple way to create a renderless component that can standardize the transitions used throughout your application. Cristi’s article goes into a lot more depth and shows some more advanced variations of reusable transitions, so I recommend checking it out.

For our other example, we’ll create a component that handles switching what is shown during the different states of a Promise: pending, successfully resolved, and failed. It’s a common pattern and while it doesn’t require a lot of code, it can muddy up a lot of your components if the logic isn’t pulled out for reusability.

So what is going on here? First, note that we are receiving a prop called promise that is a Promise. In the watch section we watch for changes to the promise and when it changes (or immediately on component creation thanks to the immediate property) we clear the state, and call then and catch on the promise, updating the state when it either finishes successfully or fails.

Then, in the template, we show a different slot based on the state. Note that we failed to keep it truly renderless because we needed a root element in order to use a template. We’re passing data and error to the relevant slot scopes as well.

And here’s an example of it being used:

We pass in somePromise to the renderless component. While we’re waiting for it to finish, we’re displaying “Working on it…” thanks to the pending slot. If it succeeds we display “Resolved:” and the resolution value. If it fails we display “Rejected:” and the error that caused the rejection. Now we no longer need to track the state of the promise within this component because that part is pulled out into its own reusable component.

So, what can we do about that span wrapping around the slots in promised.vue? To remove it, we’ll need to remove the template portion and add a render function to our component:

There isn’t anything too tricky going on here. We’re just using some if blocks to find the state and then returning the correct scoped slot (via this.$scopedSlots['SLOTNAME'](...)) and passing the relevant data to the slot scope. When you’re not using a template, you can skip using the .vue file extension by pulling the JavaScript out of the script tag and just plunking it into a .js file. This should give you a very slight performance bump when compiling those Vue files.

This example is a stripped-down and slightly tweaked version of vue-promised, which I would recommend over using the above example because they cover over some potential pitfalls. There are plenty of other great examples of renderless components out there too. Baleada is an entire library full of renderless components that provide useful functionality like this. There’s also vue-virtual-scroller for controlling the rendering of list item based on what is visible on the screen or PortalVue for “teleporting” content to completely different parts of the DOM.

I’m Out

Vue’s slots take component-based development to a whole new level, and while I’ve demonstrated a lot of great ways slots can be used, there are countless more out there. What great idea can you think of? What ways do you think slots could get an upgrade? If you have any, make sure to bring your ideas to the Vue team. God bless and happy coding.